Impressions: rasps and rifflers

We don’t often get the chance to review traditionally produced tools that are made in Italy.

So, when this opportunity came it, we grabbed it with both hands and did much more than test the tools. In fact, B&B Artigiana gave us the chance to watch every phase in the making of a rasp, from initially shaping it with a hot metal press, to punching out the teeth. We learnt that making rasps is really a craft that requires both significant metallurgy knowledge and a very fine touch. The really key moment is punching out the teeth with a burin or cold chisel before the surface is hardened. At this point, hitting a little too hard or wrongly and the tooth is too high. This might not seem like much, but when that tool comes to be used, it doesn’t work properly and nobody likes to see their work marked with grooves rather than smooth and uniform.

When we went to their workshop, aside from all the technical stuff, we were really struck by the demanding quality standards the owners aspire to, focusing on quality rather than quantity for this ancient craft. A good example of this dedication is that the staff member in charge of punching teeth went all the way to Abruzzo, in central Italy, to learn from some of the old rasp masters. The company has also proven itself to be particularly far-sighted, partnering with sculptors and other specialist artisans to improve its production and expand its catalogue through the addition of new, high performing products.

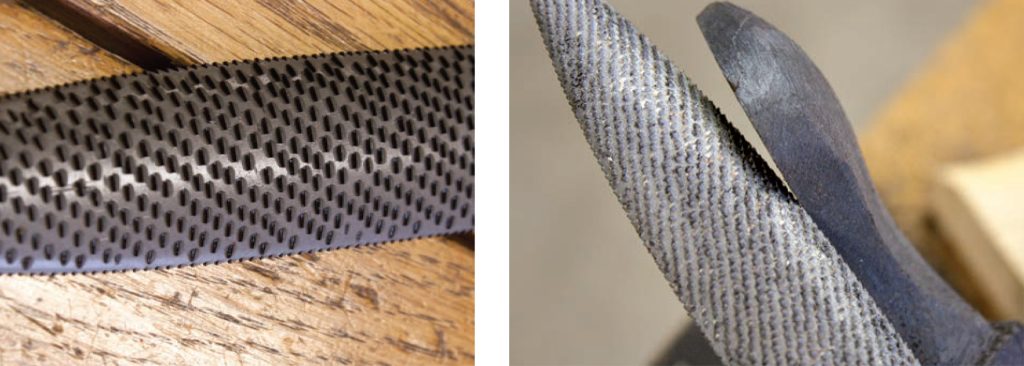

But let’s get back to the tools. We explored the most common categories: cabinet model rasps and rifflers. We were even given an experimental rasp that was very good. The base technical characteristics of the products are good. The teeth are of uniform height and density, and all the surfaces are clean and regular. The hand-crafting is clear and the non-mechanical placement of teeth suggests these tools would produce a clean result without any of the deep grooves that come from some industrially produced rasps. The rifflers come in three sizes: small, medium and large. A full range of types is available, meeting any needs for carving, sculpting or restoration work. The smaller model, with a fine cut, proved to be particularly versatile. The medium model is more aggressive, of medium roughness. The teeth are more spaced and prominent, making the start a little tough but then the tool begins to remove plenty of material.

It takes over a dozen steps to create a rasp, from shaping to hardening.

Carefully choosing the metal at the start, shaping it, precisely producing the teeth and then controlled hardening are just some of the variables that have to be faced before a reliable, lasting tool is completed.

The cabinet rasps are joined to handles in the workshop that are made of untreated wood and are produced separately. We’re very much in favour of this choice for a couple of reasons. First, many sculptors work, at times, without the handle because it makes the tool less bulky in some situations. Secondly, quite often us sculptors like to make our own handles.

The testing we did of the tools focused on the quality of the cut and the ability to remove material. The former really is the key parameter because a rasp with mid-size teeth – provided they are well sharpened – can almost be used as a finishing tool, if you use less pressure. In practice, this is like having two tools in one, which really cuts down on time and cost. Every one we tested proved to be superbly sharpened and, when working across the grain to remove wood, there was no splintering or scuffing. The actual act of cutting was good, both for compact, short-fibre wood (walnut, maple and beech) and with soft, long-fibre wood (poplar, tulipwood, and alder). On a couple of occasions, the teeth became clogged after the first few strikes. But after thoroughly removing all the gunk from between the teeth using a hard-bristled brush, the problem never repeated itself. It seems it was due to an accumulation of oil at the base of the teeth that had mixed with the wood. This is because the final step in processing the tools is to soak them in a special product that prevents oxidation. Otherwise, no other anomalies were found. The rasps are perfectly straight so they can be used for finishing joints. The teeth go right up to the end, so they can be used for finishing details or working in tight spaces.

Both the small and large models of the rifflers are best for delicate, intricate work.

The more aggressive teeth in the large model mean they are best for a medium finish, as in the picture, although with a little bit of practice, you can get good fine finishing results as well.

Testing cutting across the gain with the various cabinet models. The cut was crisp and did not splinter with any of the tools. The first two, on the left, were made using an experimental type of rasp. When the same amount of wood is removed, the surface looks more compact.

The blades are straight and well calibrated. This means they are also a good option when finishing joints. The cut from the teeth is uniform and consistent even at the tips of the tools. This means these rasps can be used for producing fine details.

Experimental flat teeth

As mentioned at the start of this piece, we also received a couple of experimental cabinet rasps. This was like a preview that I and the editors had the pleasure of trying out. The difference lies in the shape of the teeth. Normal rasps have triangular teeth and so, as they are used, they leave “V” shaped grooves that are more or less deep, depending on the model. In the experimental model, the teeth are flat. It’s a bit like a rasp being covered with a series of little panels. On first sight, it looks like removing wood is going to be hard work because, due to the width of the teeth, the wood shavings could easily get stuck. In truth, this doesn’t happen as much as one might imagine and, once complete, it is easy to clean the tool with a brush. But the real surprise was the effect on the wood. The removal of wood is comparable to a normal rasp, but the end result is significantly cleaner. The flat teeth work rather like micro-beads and, depending on how you tilt the tool, the finish is almost shiny. Performance was dramatically better when working with especially hardwoods, like boxwood and ebony. Our editorial policy is generally to avoid ending our articles with personal thoughts, but this is a bit of a special case. This is a company that has avoided offshoring and mass production in favour of quality. We went to the company and the owners definitely have concrete plans. We’ll definitely be following them closely. For the moment what can we say…well begun is half done!

A close-up of the teeth on a mid-size rasp. The teeth are parallel. This structure makes it possible to control the amount of wood removed and the degree of the finish by angling the cutting edges in relation to the direction of the fibre. The best results with this type of rasp came with very hard wood, like ebony, rosewood and boxwood. In such cases, the finish was almost shiny.

Review by: Giacomo Malaspina – Legno Lab